By Patricia Alisau

Known as the hub of the southern Panhandle, Lubbock is a college town dominated by Texas Tech University, organic food restaurants, and a trendy, new entertainment district downtown called The Depot. The locals love to brag that Lubbock is so small (population 350,000) that you can drive to anywhere in 20 minutes. And that it’s so flat and treeless that if your dog runs away, you can see him for 2 miles. The Panhandle, referred to as the High Plains of Texas, is a semi-arid rectangle as big as the state of West Virginia with a little to spare.

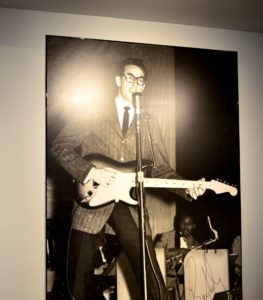

When the multi-million-dollar Buddy Holly Hall of Performing Arts and Science opens next year in Lubbock, it will be just one of many tributes due its favorite son and 1950s rock ‘n’ roll legend. A Buddy Holly Center already holds a permanent exhibition of his life from the days of parking lot gigs to performing with Elvis Presley, better known as the “Hillbilly Cat,” in those days. Holly’s breakout gold record, “That’ll Be the Day” rocketed him to fame. But his budding career tragically ended in a plane crash at the age of 22 along with fellow performers Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper. A modest granite tombstone in the local cemetery marks his grave where fans regularly leave small gifts of flowers, picks and drumsticks.

Apart from a respectable live music scene–some say that rivals Austin, Texas–in the many bars and dives in The Depot neighborhood, Lubbock has its share of oddball attractions. One is a home made of 110 tons of scrap metal called the “Steel House,” which looks more like a flying saucer with legs. But that’s where sculptor Robert Bruno, a self-taught architect, spent 30 some years building it and only living in it the last seven months of his life. A tour of the three-story, 2,200 square-foot interior reveals a pure form of organic architecture with unusual curved rooms with long curving windows, stained glass, a South American olive-wood staircase and imperfect tiles.

Not so oddball is the town’s growing wine business and one of the popular vineyards is Llano Estacado, the name Francisco Vazquez de Coronado gave the region in the 16th century when he swept through looking for gold. One of the oldest wineries started by two university professors in a shed, its Merlots and Chardonnays are top prizewinners in state competitions and a wine tasting tour will introduce other selections from their vines. A newcomer is a red with Dr. Pepper overtones created as a nod to the popular Texas cola.

A two-hour drive north of Lubbock crosses over into the northern High Plains of the Panhandle and Amarillo. It’s a boots ‘n jeans kind of place, is a little bigger than Lubbock and closer to New Mexico, Colorado and Oklahoma than to any of the major Texas cities.

While towns like Lubbock have a growing organic cuisine movement, Amarillo sticks to the basics with down home grub like the heralded 72 ounce steak dinner at the Big Texan Steak Ranch. Hard core eaters get it free if they finish it along with the sides in less than an hour. Otherwise, they pony up $72 for the meal. Started in the 1960s by the Lee family, it began as a diversion for cow hands, who walked away with nothing more than bragging rights as a prize. But that was incentive enough to keep it going. Apparently gender doesn’t matter either. Danny Lee, one of two brothers running the restaurant, recalled when a 118-pound woman wolfed down a meal in 20 minutes.

Originally located on iconic Route 66, the Big Texan moved in 1970 to a bigger highway when it supplanted ’66. Although the heyday of the route is long past, it still marks Amarillo as the nearly halfway point between start and finish, between Chicago and Los Angeles. An historic one-mile stretch on Route 66 in downtown Amarillo is filled with repurposed saloons, shops, a biker cafe, and restaurants, which keeps the story alive and is a great place to buy memorabilia of the era. Most of the rest of the 30-mile route is largely abandoned with shuttered motels, bars, gas stations, and a night club touting the “big band sound” of the ’50s. But one enterprising businessman turned an old motel into an Airbnb. And just out of town, the Cafe at Adrian claims to be the exact mid point of the old road and does a brisk business in homemade coconut pies. In all, Route 66 represents a milestone when America transitioned from dirt roads and Indian trails to today’s superhighways.

Amarillo’s answer to quirky attractions is the fun Cadillac Ranch, a bunch of side-by-side caddies buried nose deep in the dirt like a Texas version of Stonehenge. Apparently, it was inspired and funded by local philanthropist Stanley March III who hired a San Francisco design firm called The Ant Farm to pull it off. Around since 1975, you can’t miss it from the highway and once you’re through the gates, you’re encouraged to spray paint the Cadillacs to your heart’s content along with the other budding graffiti artists.

A high point to any visit is Palo Duro State Park, a rugged red sandstone canyon on record as the second-largest in the U.S. It’s an easy drive 25 miles southeast of Amarillo. For a musical snapshot on the Panhandle’s Old West days, you can book tickets for “Texas,” a live Broadway-style production in the park’s amphitheater in summer months. Stargazing is superb as well as the 40 miles of hiking, biking and equestrian trails. If you’d rather see the canyon from the air, a new zip line will take you soaring over it. One of the first takers was a 103-year-old woman, so age is no limit and neither are wheelchairs as two of the ramps are outfitted with them.

Back in the day, the canyon was sacred ground and headquarters for the Comanche empire, which held it for a century and a half before being driven out by the US Calvary in 1874. Their renowned leader, Quanah Parker, whose mother was Cynthia Ann Parker, is legendary as a fierce warrior and his name is still spoken with respect in these parts.

Another legend and a close friend of Parker’s is Charles Goodnight. Together, the two of them helped save the buffalo from extinction, which were almost wiped out from hunting when Charles Goodnight arrived in the 1870s to start a cattle ranch. Descendants of the original herd can still be seen at his museum-home 40 miles from Amarillo. As a boon to his cowboys, Goodnight invented the chuck wagon, which kept them fed on long cattle drives. Cattle and a new railroad spurred the founding of Amarillo a decade later.

Whether its cowboys, Comanches or conquistadors, Lubbock and Amarillo represent the unique culture of the Texas Panhandle and can be visited separately or as a duo.

How to Get There: Lubbock and Amarillo have airports served by major airlines.

Best Time to Visit: The spring and fall are best for more comfortable weather. The summer months can be hot, hot and hot and nighttime in winter can dip below freezing.

For more information: www.visitlubbock.org and www.visitamarillo.com