Voters won’t use the health of the U.S. economy as a measuring stick when they decide whether to extend Donald Trump’s presidency six weeks from now, according to an expert who studies politics and government in the critical swing state of Ohio.

Unemployment rates in swing states have thrown the usual political calculations overboard. Millions of Americans saw the economy declining measurably during the Covid-19 pandemic’s early months. But voters, including those already casting ballots by mail, might let the White House off the hook.

“I would argue, it’s not going to affect anything,” said Brianna Mack, assistant professor of politics and government at Ohio Wesleyan University. “It’s not like pandemic politics anymore. It’s back to identity politics.”

Mack thinks Republicans could try to blame the economic situation on the pandemic or even potentially on demonstrations and rioting. “Fears about the disease as well as fear of defunding the police will keep voters from holding the incumbent responsible,” she said.

There is also a practical issue: The people hurt most by unemployment are the poorest Americans who vote less reliably than those in the middle class.

“You’re not going to get out of a line to get into a homeless shelter to go vote,” Mack said. “You’re trying to make sure you can secure a cot for yourself or your children for the night.” Or they may be tied up with work and unable to afford child care before or after hours to cast a vote, she said.

“So we end up in a Catch-22,” said Mack. “We can see that play out again this year. It doesn’t get any easier.”

Presidential campaigns in the past have risen and fallen on economics questions. Bill Clinton’s 1992 catch-phrase became “It’s the economy, stupid.” Ronald Reagan asked voters in 1984, weeks before a landslide re-election, “Are you better off now than four years ago?”

A Zenger News analysis of unemployment data for likely battleground swing states suggests a mixed bag. Unemployment insurance filings and official unemployment rates, both for the country as a whole and for battleground states, show widely varying and sometimes conflicting results.

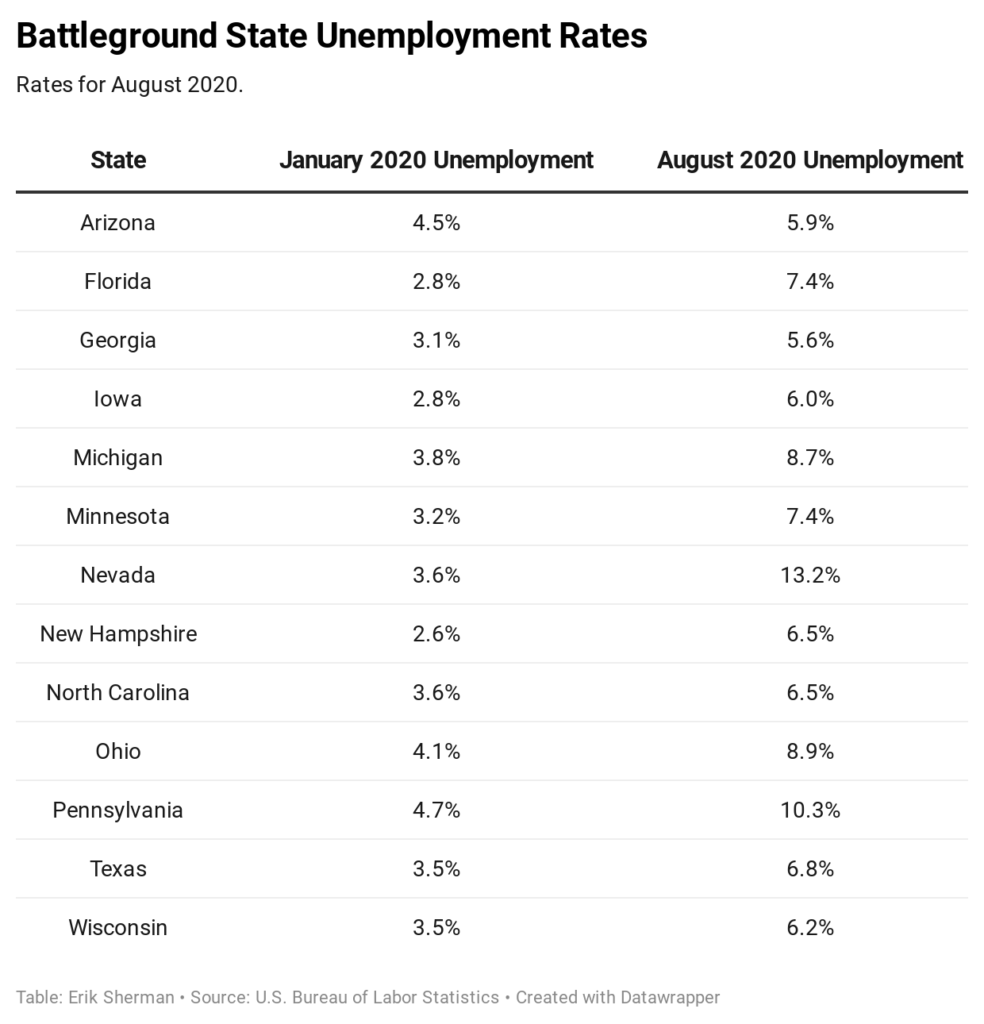

Although unemployment rates have dropped significantly from their highs in April and May, most states are a long distance from where they were at the opening of 2020. January and August unemployment rates for the 13 most likely swing states tell the story of an economy growing more slowly than anything Trump could crow about.

Even with more people going back to work, unemployment is high compared with the beginning of 2020. Current rates in battleground states are anywhere from one-third higher (Arizona) to 3.7 times as high as in January (Nevada).

Those rates, though, can be deceptive.

The Job Loss Shuffle

The federal government uses several different measures of unemployment, all gathered through surveys the Census Bureau regularly administers. The official rates the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes every month the so-called U-3 rates include only people without a job who have actively looked for work in the previous four weeks. Looking through job listings and finding nothing doesn’t count.

Other people who are out of work aren’t included in the U-3 numbers. Those include Americans who can’t get full-time work because employers aren’t offering it, people who want work and job-shopped within the past year but not in the last four weeks and those who aren’t looking at all because of the state of the job market.

“You can have a number as low as 12% of unemployment when the real number is 22% or 23%,” said Giacomo Santangelo, a professor of economics at Seton Hall University and a senior lecturer at Fordham University.

According to the U-3 measure, the number of unemployed in August was just under 13.6 million. Yet the bureau also says that in August, “24.2 million persons reported that they had been unable to work because their employer closed or lost business due to the pandemic. Those Americans did not work at all or worked fewer hours at some point in the last 4 weeks due to the pandemic.”

Just under 12% of that group received at least some pay from their employers for what the government calls “hours not worked.” That includes holidays, sick days and work performed off the clock. About 5.2 million people said they couldn’t look for work because of the pandemic.

Unemployment Insurance Line

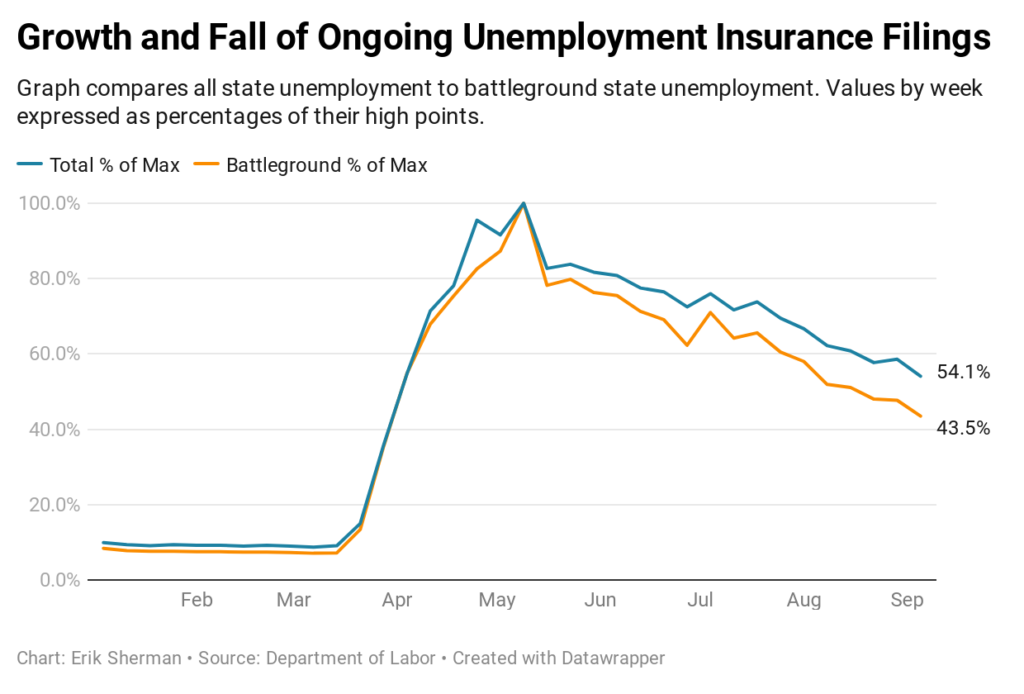

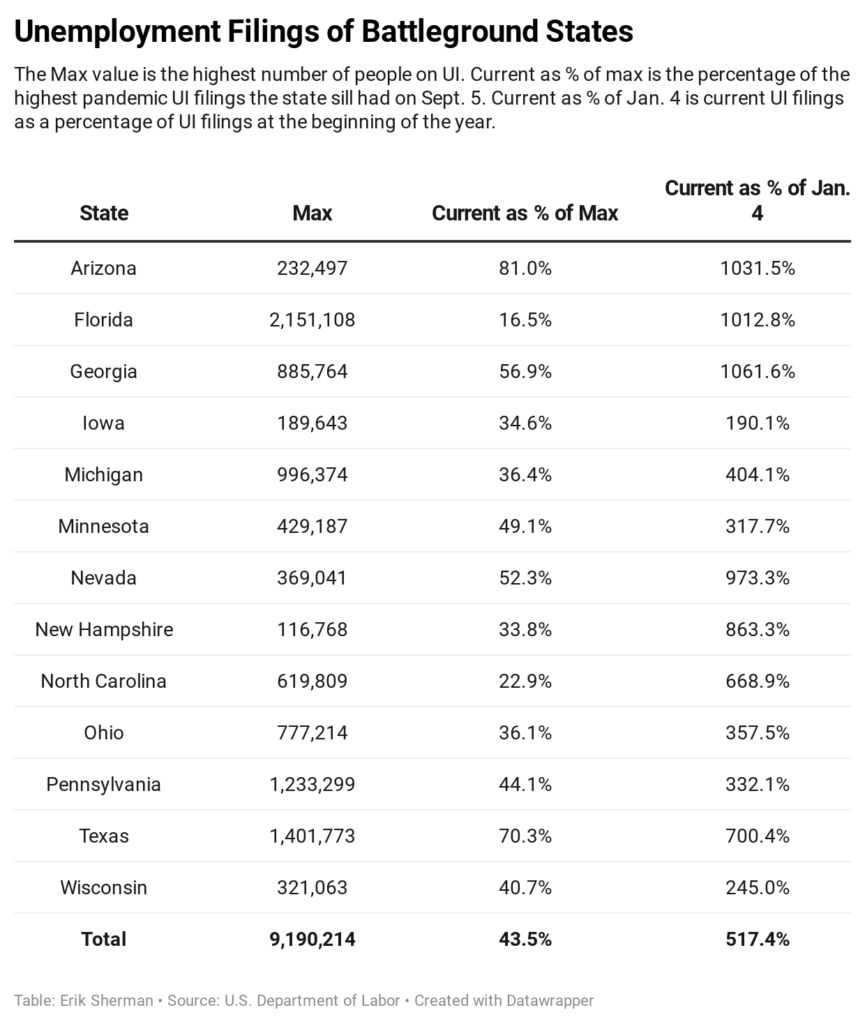

Another way of looking at unemployment is through the lens of people who have registered for unemployment insurance. There are multiple unemployment insurance programs, but among the most basic are those run by states. A Zenger analysis of people who continue to be registered for unemployment insurance compared the growth and decline of filings from Jan. 4, 2020 through Sept. 5, all as percentages of the highest rate achieved during the pandemic.

Most of the battleground states still face high levels of unemployment filings. Florida is the biggest exception, but that could be explained in part by a strategy that Governor Ron DeSantis has said relied on to “pointless roadblocks” that drives people to give up and not be eligible for benefits.

(Edited by Allison Elyse Gualtieri and David Martosko.)

The post It’s Not ‘The Economy, Stupid’: Voters Might Forgive Trump for Covid Job Losses appeared first on Zenger News.