By Eduard Ribas i Admetlla

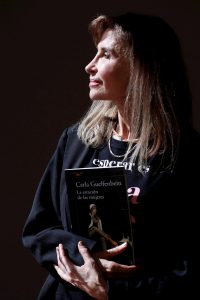

Guadalajara, Mexico, Dec 1 (efe-epa).- Chilean author Carla Guelfenbein, in discussing her latest work, “La estación de las mujeres” (The Women’s Station), says that her novels have always been feminist but until now she could not say so openly.

“Is this a feminist novel? Yes, of course. I think that all my novels are feminist, but the only thing is that until now I was not allowed to say so,” the winner of Spain’s prestigious Alfaguara Novel Prize in 2015 told EFE during the International Book Fair (FIL) in Guadalajara, Mexico.

Guelfenbein, who was born in Santiago in 1959, said that a decade ago she had to defend herself “tooth and nail” when her novels were called “feminist literature” and writers had to try very hard to get “the patriarchy to accept us,” she said.

“Nowadays, women are tired of waiting and we say we’re part of the canon and, if not, that canon doesn’t interest us,” she said, adding that she began writing her latest novel four years ago when “the feminist demands were not as prevalent as in the last year-and-a-half.”

Although it wasn’t something premeditated, “La estación de las mujeres,” which tells the parallel stories of six women whose lives are intertwined, Guelfenbein is joining the “current, important and necessary discussion” of feminism.

However, she insisted that she doesn’t view novels as a tool of political activism since “literature is much more than a (political) pamphlet.”

“I think I’m closer to literary truth when a person contradicts me and feels something that goes against my principles,” she said, noting that she uses other platforms – including press articles – to express her opinions and “participate actively as a citizen.”

In this novel, the writer takes a certain “liberty bordering on transgression,” since she mixes fictional characters with two real women: Chilean poet and pedagogue Gabriela Mistral, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 18945, and Mistral’s partner, US writer Doris Dana.

“All these characters began to form around a geographical space and ideas. So, they transformed themselves into part of this ‘collage,’ which is the novel,” she said.

Guelfenbein has actively participated in the recent protests in her country, which began as a popular rejection of the hike in Santiago metro fares but morphed into a massive mobilization that has forced President Sebastian Piñera to announce the drafting of a new constitution.

“It’s absolutely necessary to abolish the illegitimate constitution created by the dictatorial government of (Augusto) Pinochet to protect neoliberalism,” said the writer, who in 1976 fled the dictatorship and went into self-exile in England with her family.

She said that for decades Chile was experiencing “a situation of neoliberalism with a pretty face and a pink dress,” such that Chileans themselves convinced themselves that they were a “Latin American oasis” of calm, economic prosperity and good governance.

Guelfenbein, who defines herself as a pacifist, said that now it’s “very nice and emotional” to be able to participate in the citizens’ groups that gather in Santiago’s plazas to debate the elements of the new constitution, adding that it’s necessary for the government to give “a clear and unequivocal sign that the system is going to change.”

“Piñera has not provided that sign because he’s … a coward and an idiot,” she said.

The FIL is considered to be the world’s largest Spanish-language book fair.