July 12, 1995

By Yolanda Reynolds

Exhibit at American Indian Center

“Following Direction, Skin Alter,” a multi Cultural Art Exhibit by Native American artists of various tribes, residence, and descent showing at the American Indian center of Santa Clara Valley, presents an outstanding collection of artwork that breaks new ground, both artistically and thematically without rejecting Indian origins.

Many of the artists whose works are on exhibit are either attending or have attended the prestigious American Indian Institute of Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

There is the work of James Rivera a San Josean and descendant of the Arizona Yoeme tribe. One piece, “Bear Dreams,” an oil on canvas, is hauntingly beautiful. The “dream” could be the bear’s own dream for the past when bears, now endangered in much of the world, had dominion of the forests and streams. It could also be a majestic representation of what the bear has traditionally meant to indigenous peoples — a being of great strength and importance in the totality of life.

On exhibit are several other pieces by Rivera. The piece entitled “Bear Protection” is a stunning piece for its simplicity and the power evoked by the spare use of color in what is basically a flat metal sculpture.

Rivera has one more year of study at the Institute and following an additional two years of studies needed for a Bachelor degree in Fine Arts, hopes to teach art to the children of his tribe at the Pasqua Yaqui Reservation in Arizona. Some Congressional members are suggesting to defund the Institute which would imperil the studies of many current and future students.

A number of pieces in the exhibit address the continuing impact of the abrupt and dramatic change in the lives of all indigenous peoples upon the arrival of the Europeans.

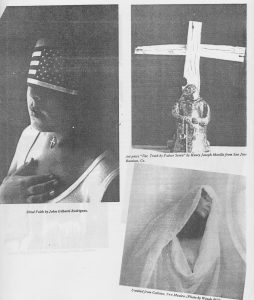

Several pieces by a San Jose artist of Ohlone-Chumash ancestry (San Juan Bautista), Joseph Henry Morillo, portrays the feeling of many observers that indigenous tradition, and indeed their lives, were sacrificed on the altar of Christianity upon the conquest of this land. These pieces ar thought provoking with every element of the work adding a significant insight.

A delight to the eye and a graphic example of the merging of tradition in a new expression is the delicately beautiful pottery by Glenda E. Loretto, a Jemez Pueblo Indian of Northern New Mexico.

On exhibit is an example of the traditional method of pottery making along with a traditional “wedding vase” pot however it is made using the “raku” method of firing pottery. Regardless of the method, Loretto’s inclination is to insert an element that makes her pottery unique.

There are those, both Native American and non-Indian, who think that “Indian” art should only follow a pattern and design that someone in the past has declared to be “Indian Art” – whatever that means. Others feel that “Indian” style and art is capable of further growth and development.

The debate goes on. By their work, these young artists are presenting their artistic expressions in ways that declare their presence and force of energy in anticipation of the 21st century.

In defense of and in the search for Native American artistic talent there are those who say not all (Indian art) is “end of the trail” art work. This exhibit proves that Indian art is diverse and not static but at the same time these artists do not deny the richness of their distinctive indigenous heritage.

One piece, “Rez Dog,” by Joseph Henry Morillo must not be missed. Anyone who has visited a pueblo on the reservation can recognize this “dog.” This spare sculpture is loaded with humor and pokes fun at the many extremes to which Indian images are taken by some tourists.

The artists themselves are representative of the reality of life for both those of indigenous peoples. There is, on exhibit, the provocative and artistically beautiful photography of the Chicano Vietnam veteran and San Josean John Gilberto Rodriguez.

There are a number of his photos, all good, all in black and white. One entitled “Blind Faith” and of a young person whose eyes are covered with a U.S. flag. The viewer can draw a variety of conjectures as to the major image this photo illustrates. This photo could be used not only as a photographic example of the use of light and shadow, but it could be used to inspire a lively political discussion.

Art work by Jimmy Arterberry “Pe Ve Ah Ne Ah Wok” is an oil on canvas on which a slightly blurred buffalo seems to be airborne behind a feathered medicine shield. The colors, texture, balance and subject are riveting but pleasant to behold.

Arterberry, is a Comanche and is highly regarded not only by art collectors but by his own Comanche community. A Comanche art dealer in Norman Oklahoma, Pahdopony says of Arterberry’s work. “His artwork has had a significant impact on visitors because they reflect sensitivity, awareness of the richness of Comanche culture, and make statements of contemporary views of the artist and his experience of the culture.”

Arterberry’s work is represented in the permanent collection of the Institute of American Indian Art Museum at the Plaza of Santa Fe New Mexico. He has sold numerous works of art to dealers serving private collectors.

This collection of artists, ranges from those who are now “urban Indians” to those whose whom the home base might be an Indian reservation and others who hail from places as far apart as Copper Center, Alaska and Bogota, Colombia and anywhere in between.

This is an exhibit that no one should miss seeing even though this outstanding showing suffers from a lack of the space and proper lighting to best show off these beautiful pieces of artwork.

The exhibit was assembled by Joseph Henry Morillo who says that he was driven to get this exhibit together so that Native American artists including those who hold a close identification with their dual patronage – Native American and European – can break away from confining boundaries and express what they are feeling today and explore the future with-out limitation by notions of what is acceptable imposed by a static idea of “tradition.”

Other artists whose work is on exhibit are; Don Meeks, Charlie Chino, Rich Moreno, John Joe, Andrew Corredor, Marvin Garcia, Jack B. Sabon, Wende Williams. One of the few non-American Indians at the Institute is Tommomi Kumakura from Tokyo, Japan who completed her studies in creative writing at IAIA this past year. Kumakura is now a published poetess. Her poetry was highly regarded by her instructors who recommended her work for publication in the Institute’s quarterly publication during every semester of her studies in Santa Fe.

The Santa Clara Valley American Indian Center is located at 919 the Alameda For more information contact the center at 971-9622. © La Oferta Newspaper.